Unlike his criminal contemporaries, Jack Kennedy’s career (both criminal and legitimate) was always tied to the railroads.

In the last installment I told you all about Jack’s supposed first exposure to the art of train robbing, when Jesse James held up the Chicago & Alton train passing by the Kennedy family farm in Crackerneck (Independence, MO). Young Jack held onto the memory of that night in 1879 as he left Missouri for Houston, Texas to start his own adventure around 1886. His first job that we know of was operating as a bartender in Houston saloon, but his habit of drinking the merchandise and handing out free samples soon forced a career change.

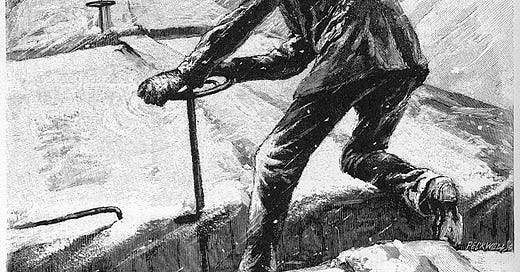

Soon after, Jack was given a job with the Southern Pacific Railroad. He held a number of positions as he worked his way up the career ladder of a railroader. The exact timeline of his career with the S.P. is unclear and I am actively working to recover any official documents detailing his employment. Thankfully a number of stories have circulated throughout the years, some more myth than reality I am sure but such is the way of these things. Jack began his railroad career as either a fireman or a brakeman, it is unclear which came first. A fireman’s position on the train is to coordinate with the engineer to maintain the fire fueling the locomotive by adding coal when needed. A brakeman stands atop the train cars and turns the manual brakes located at the end of the roof of each car. Typically two brakeman would work each train. When it came time to slow down the two workers would start from either end of the train, turning the brakes of each car and working their way towards the middle. This process decreased the chance of derailment as the train slowed at a more even pace.

The story of Jack’s foolhardy nature as a fireman can be found in the February 1911 edition of The Railroad Man’s Magazine, a copy of which you can view below.

I beleive this story was initially told by Leroy “Chalky” Foote, a Chicago & Alton engineer familiar with Jack’s early career and who was himself held up by Jack numberous times on the Blue Cut line. It is recounted here by Gilson Willets, special traveling correspontent for the magazine. The story goes as follows:

One day, on the run between Indepenence and Kansas City, the train was late. Suddenly, Kennedy turned to the engineer, saying: “Clark, is your life insured?” “Yes.”

Without another word, Kennedy seized a monkey-wrench, climbed out on top of the cab and screwed down the safety-valves. “Now let her go!” he shouted to Clark. Engineer Clark protested, but Kennedy said:

“You stick to the throttle and leave my work alone or I’ll throw you out of the cab.”

Good fortune favored them, however, and the train ran into Kansas City on time. “You’re certainly the limit for recklessness, Kennedy,” said Clark. “What would you do if our train was to be held up some night? Refuse to throw up your hands and shoot?”

“No,” replied Kennedy. “I’d join in the hold-up. There’s more money in that than in railroading.”

This story certainly established Jack as an impulsive yet clever young man eager for a thrill whenever possible.

It would appear that his disregard for safety may have caught up to him, however, when he worked as a brakeman. At some point during his brakeman career he was present for a massive train derailment. When the train cars toppled over, Jack fell from his roost atop the cars and had one of his legs partially crushed beneath the many tons of steel. After a breif recovery he was promoted to engineer of a freight train and later a passenger-train that ran overnight. Jack walked with a noteable limp for the rest of his life, something that rarely hindered his ability to rob a train but often gave away his identity afterwards.

The last noteable story I have found so far also comes from the pages of The Railroad Man’s Magazine and further highlights Jack’s brazeness.

Soon after being given charge of the overnight passenger-train, Jack decided to chase another passenger train directly in front of him. Mind you, these are trains on the same track and not like cars driving on the same road that can weave and pass each other. Jack gunned the throttle until his locomotive was merely feet away from the rear platform of the other train.

As they neared Independence, where the leading train was scheduled for a stop, neither train slowed even a bit! The outlandish speed and closeness of Jack’s engine to the other meant that any decrease in speed could result in a calamity. Both trains flew past Kennedy’s home-town in a flash of steal and steam! The station agent frantically wired all stations westward to Kansas City that two trains were running wild. The Kansas City dispatch was surely filled with panic and confusion as they tried to clear oncoming tracks and find some way to slow the two machines gone mad.

Jack chased the train all the way into Kansas City. Upon his arrival the railroad company quickly fired him and had him arrested and held for ten days under the charge of “malicious mischief.” That term would prove an accurate description of Jack’s career from then on out.

While I don’t wholly doubt the validity of this story, I’ve yet to find any solid documentation to corroborate it aside from recollections and retellings decades after the fact. For instance, in the Railroad Man’s Magazine it is noted that Jack worked for the Missouri Pacific Railroad while most other sources say the Southern Pacific Railroad. It is possible he worked for both, moving from the S.P. when he was in Texas to the M.P. when he moved back home. There is also some conflict with the nature of his firing from the railroad.

It is widely noted that Jack met former James gang member Bill “Whiskeyhead” Ryan (aka William Jennings) shortly after Ryan was released from the Missouri State Penitentiary in 1889, having served time for the same 1879 robbery that Jack recalls hearing as a boy. It is often stated that Jack was suspected of befriending Bill Ryan in that period and this lead to him being suspected of committing a number of robberies on the Southern Pacific line he worked. He was so heavily suspected of having taken part in a 1892 robbery that some sources, including Chuck Rabbas’ book, claim this was what lead to his firing. Granted, neither Rabbas nor Rauh mention these railroad misadventures in their books, so I’ll have to piece together the whole story as more evidence gets tracked down.

Thus ends Jack’s legitimate career and thus begins his more famous and more lucrative time as a robber-bandit of the rails. I hope you enjoyed this entry of Hunting the Quail Hunter! Finding any documentation related to Jack’s early life is difficult but I am pursuing a number of leads that I hope prove fruitful. In an upcoming installment I may include a “call to action” of sorts highlighting some of the documents or claims I am currently digging for that you all could lend a hand with, if you so chose. I spend alot of time going through microfilm of newspapers, searching various online databases, and calling a variety of historical societies and museums. If you’d like to help with any of these efforts I am more than open to it! With that, I look forward to the next installment and hope you all do too! Be sure and subscribe if you haven’t already and please share this wherever you can and with anyone you think may find it interesting!

Until next time,

Cam